2.3.

Human-Human-Interaction

The usual way humans interact with each other is face-to-face and by language.

In such a communication at least two humans exchange meaning verbally. But

words and sentences are not the sole part of the communication. Potentially

humans can communicate with all five senses: sight, sound, touch, taste and

smell. Using these channels, many other cues, verbal and non-verbal, are incorporated

when transferring meaning. The sender employs these cues subconsciously and

the receiver understands it in the same fashion - subconsciously. A vital

feature is that our everyday interaction with each other and the world around

us is a multi-sensory one, each sense providing different information that

builds up the whole.

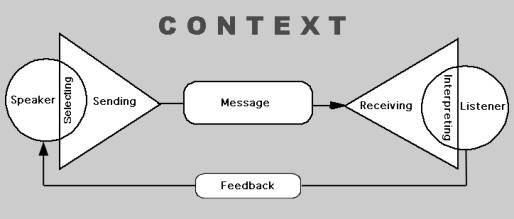

Let's have a closer look on human-human communication. A key issue in interaction

is language. It is not a one-channel but always a two-channel process. The

sender utters some words complemented by gaze, The receiver gives back some

kind of acknowledgement to the sender, poses questions or takes turn, i.e.

there is feed-back channel (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The sender-receiver model of human

communication

The fluency, prosody and intonation

of the sentences and words tell us important things about the speaker, e.g.

about his inner state, about the circumstances he is speaking of or to give

or emphasise a certain meaning. A closer look on language in dialogs brings

up five main human abilities to successfully participate in conversation (CMT3210).

1.

An important aspect of communication is the human's ability to recognise

openings and closings of topics during a conversation. It guaranties that

both persons keep track on each others contexts to advance the dialog or avoid

misunderstandings.

A: Do you want another

pint? opening

B: what's the time? opening

A: ten to ten closing

B: OK, yes thanks closing

2.

If a misunderstanding should occur, a second 'basic' technique jumps in:

repair actions. Using questions or non-verbal cues they try to clarify the

questionable fact or the context it is embedded in.

3.

Humans exhibit context sensitivity when interacting with each others. They

can understand the meaning of the words in a certain context, be it the actual

situation the fact is told or a certain (fictitious) setting, e.g. the last

holiday.

4.

To keep the conversation

going, humans use short sequences of feed-back cues and turn-taking signals.

First show to the speaker that the listener is following the speaker's pace

of thoughts, e.g. a nod or mumbling 'Hmmm'. Latter signals to the listener

that he might take turn and begin to speak, e.g. a pause and looking into

the eyes.

5.

If the communication

situation provides more than two people, it can happen that the original speaker

hands over 'his' conversation with the second human to a third one, who takes

up the talk. This concept incorporates adjacent pairs of action and response.

A: who is speaking? action

B: it’s Bob Fields response

C: is he going to the US? action

D: well, I heard that

….

response

The relationship and interplay

between these abilities make it happen that humans understand such concepts

like humour, sarcasm and irony. Humans can detect if there is a mismatch between

the literal word, it's meaning (semantics) and what the speaker wants to tell

(pragmatics). In humour, sarcasm and irony the pure words never transport

the true meaning, but intonation, pauses and prosody may hint on the speaker's

intention. They listener has to have some background knowledge fitting the

speaker's one to decode the message. Otherwise misunderstandings are likely.

Aside from the language centred

cues there are multiple sources of sensory information, the so called non-verbal

cues. These cues could support or complement the verbal utterances, e.g. pointing

somewhere and saying 'there!'. It includes gestures like hand movements, head

and eye movements as well as body movement and body orientation. Non-verbal

cues can be expressions on their own, i.e. the body language. Turning your

back on someone and crossing the arms in front of your chest will tell anyone that you don't

want to interact with this person even if you don't say a word. On the other

hand, when someone identifies a known person, the typical reaction is tracking

with the eyes and a body orientation towards the person in question. That

will be understood as a sign of openness and the disposition to start a conversation.

Non-verbal cues play an important role for both, the speaker and the listener.

For the speaker they are necessary means to accentuate his story. They support

the listener to understand what the speakers wants to tell. Without non-verbal

cues the conversation would be 'stiff' and quite unnatural.

An

important aspect is the context of the conversation are the emotional states

of the participants. They play a key role to truly understand what each one

wants to tell. Thus the ability to recognise, interpret and express emotions

- commonly referred to as "emotional

intelligence" (Goleman, 1995) - plays a key role in human communication.

Related is empathy, another typical property of human-human interaction. It

means that someone shows understanding of the other's situation and is feeling

with the individual, e.g. after a friend has suffered from a great loss one

could express his sympathy by simply hugging him.

[CG1]

Without showing some kind of empathy the human-human conversation is cold

and distant, solely consisting of facts - not any social. This is how we have

to interact with computers today. To see how we could bring social factors

into this interaction, let us have a closer look on the status quo of Human-Computer

Interaction in the next chapter.